Complete History of Jerónimos Monastery

From royal vow and spice routes to UNESCO recognition — the story of Lisbon’s stone lace by the Tagus.

Table of Contents

Royal Vow & Maritime Belém

At the dawn of the 1500s, King Manuel I chose Belém — the riverside threshold of Lisbon — to plant a monastery that would give thanks for voyages and pray for sailors. The Age of Discoveries had braided the Tagus to oceans; spices, maps, and stories returned to this shore, and a royal vow took the shape of stone.

The site mattered: near a small chapel where Vasco da Gama and his crew are said to have prayed before departure, close to shipyards and the river’s steady light. Jerónimos rose as both cloister and chronicle, a place to fold the sea into prayer and bind empire to responsibility. Manuel’s emblem — the armillary sphere — and ropes carved in limestone announced a maritime language made sacred.

Construction, Craft & Materials

Diogo de Boitaca began the work, his plan setting a wide‑armed church and a cloister that feels endless underfoot. João de Castilho carried the project forward with virtuoso carving; later, Diogo de Torralva and Jerónimo de Ruão refined proportions and classical accents as tastes shifted. Years stretched, stones stacked, and a style took on weight and grace.

Golden‑hued lioz limestone records the carvers’ patience: knots and ropes, coral and leaves, saints and royal signs. Vaults leap with startling lightness; columns unfurl like trunks into canopies. The craft feels intimate even at monumental scale — a city of detail you can read with your fingertips.

Manueline Language & Architecture

Manueline is not a single motif but a vocabulary: armillary spheres, crosses of the Order of Christ, twisted ropes, shells, seaweed, knots, pinecones, and fantastic creatures. At Jerónimos, this language blooms into structure — tracery and capitals, portals and parapets, all speaking of ships and scripture in the same breath.

The church interior makes stone feel light: a hall of branching columns whose vault seems to hover. The cloister turns the page and invites you to walk and read — shadow after shadow, arch after arch — until the sea seems to echo in the geometry. It is architecture as embroidery, faithful and fearless at once.

Prayer, Poetry & Symbols

Monastic life once wove the day here — bells and psalms, bread and study. Later centuries layered poetry and public memory: the tombs of da Gama and Camões in the church, royal burials in the chancel, and tributes that read like footnotes to a long maritime chapter.

Symbols abound but never shout: a rope can be a prayer for safe passage, an armillary sphere a map of wonder. Walk slowly; the carvings speak in a low voice, and the courtyard answers with light.

Secularization, Preservation & Restoration

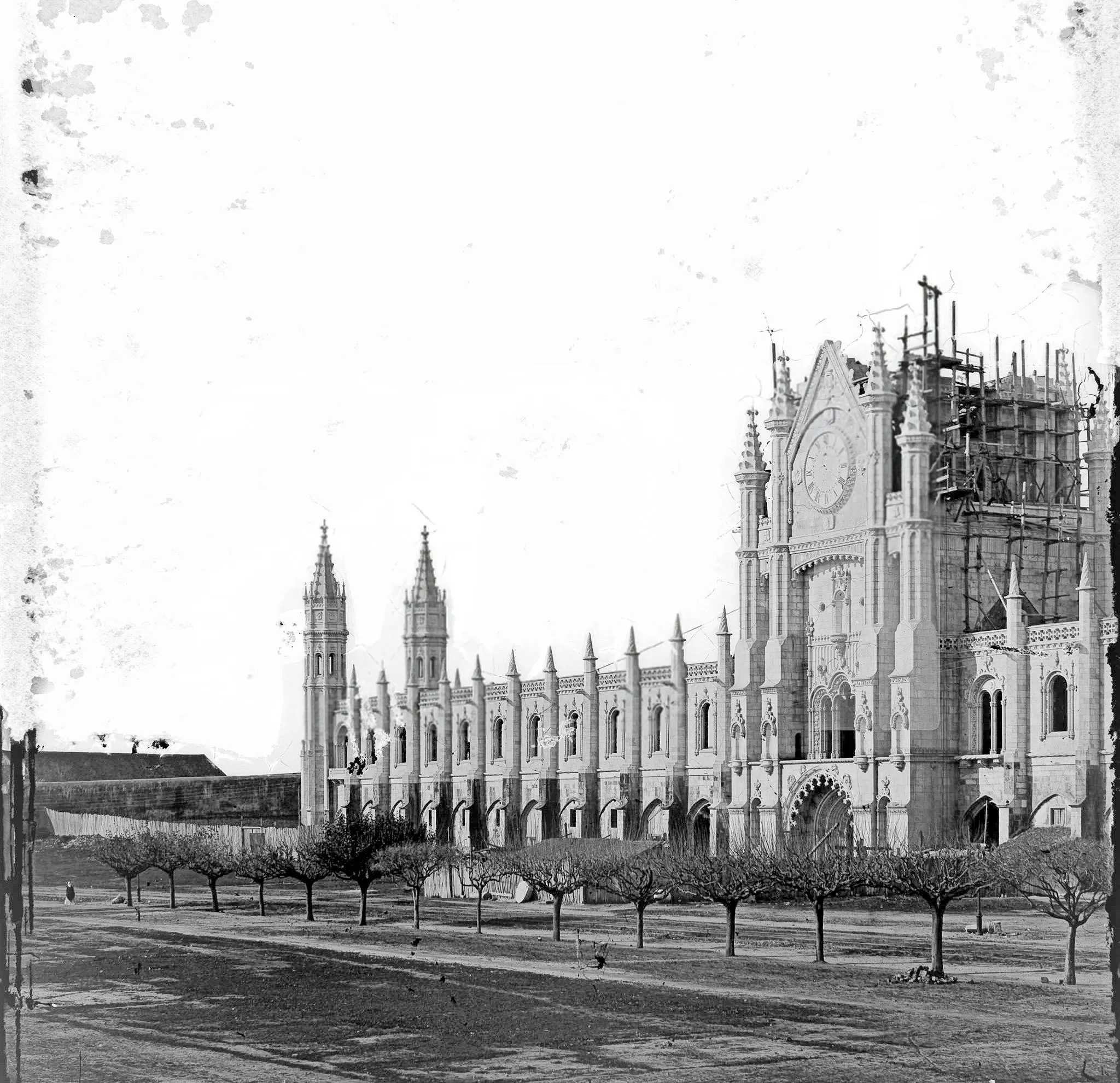

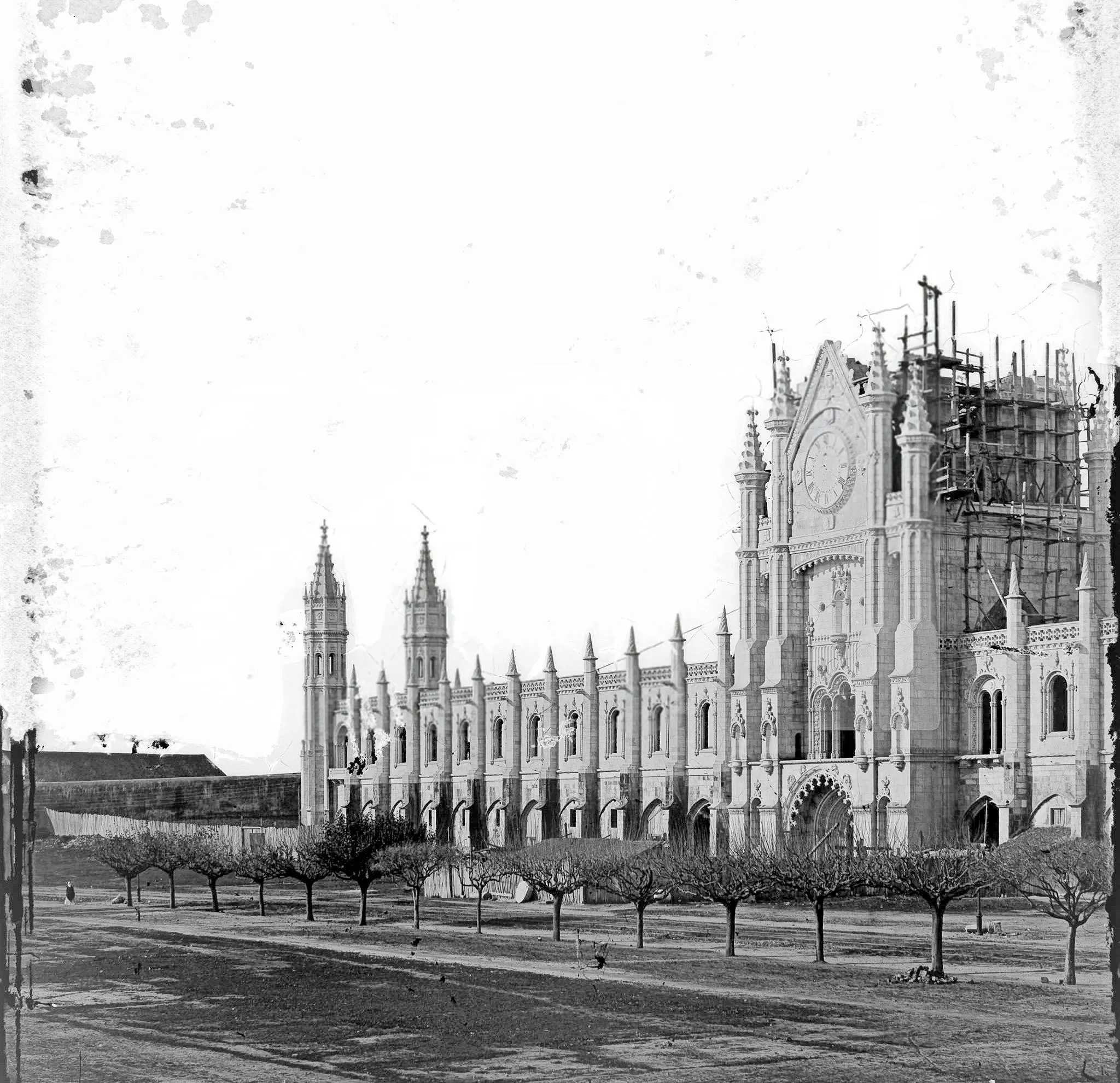

Religious orders were dissolved in the 19th century; the monastery’s function shifted, even as its fabric remained. Earthquakes tested Lisbon, but Jerónimos endured with scars and grace. Restoration became a slow craft — cleaning, consolidating, and letting the stone keep its warmth.

Conservation here is a conversation with weather and history: joints repaired, carvings protected, drainage improved, access widened. The goal is legibility and calm — to keep the monastery readable without whitening away its years.

Ceremonies, Treaties & Memory

The monastery has hosted ceremonies of faith and state — from liturgical moments to cultural events. In recent times, it has framed European milestones, including the signing of the Treaty of Lisbon, binding the cloister’s calm to contemporary history.

Media and visitors carry these images outward: arcades, flags, and the river’s light. The building remains a setting for gratitude, debate, and quiet pride.

Visitor Experience & Interpretation

Guides and panels help decode Manueline motifs; audio tours stretch the thread from rope carvings to ocean routes. Families, school groups, and solitary wanderers find their own pace between sunlit stone and cool shade.

The rhythm of a visit is gentle: lower cloister, upper cloister, church, then a quiet sit on a bench. Interpretation favors clarity over noise, letting the monastery’s voice remain calm and kind.

Empire, Earthquake & 19th Century

Empire waned and Lisbon trembled in 1755; Jerónimos weathered shocks that leveled districts elsewhere. The 19th century brought secular shifts and a growing sense of heritage, with careful repairs and new respect for the Manueline voice.

By century’s end, restoration leaned toward revival and preservation. The monastery settled into its role as a national symbol — a patient witness to change.

20th Century: Nation & Heritage

The 20th century framed Jerónimos as cultural heritage as much as sacred space. In 1983, UNESCO recognized the monastery and Belém Tower, underscoring their global significance and maritime memory.

Conservation matured into a discipline of patience: surveys, gentle cleaning, structural care, and better visitor paths. The goal: keep the monastery alive and legible for everyone.

River, Route, and Global Ties

The Tagus is a chapter in the monastery’s book: ships slid past Belém with sails full and hearts uncertain. Jerónimos kept their names and prayers, anchoring a city to seas and stories far beyond its harbor.

Walking the cloister today still feels connected to routes that circle the globe — a reminder that stone can hold both home and horizon 🌍.

Women, Scholarship & Heritage

Modern scholarship widens the lens on monastic life, patronage, and the city around Jerónimos — bringing into focus the women who funded, worked, and interpreted this place across centuries.

The result is a richer story: not only kings and sailors, but artisans, scholars, and communities keeping a monastery alive in memory and care 🌟.

Nearby Belém Landmarks

Belém Tower (Torre de Belém), the Discoveries Monument, the MAAT and Berardo Collection, the National Coach Museum, and the riverside gardens make easy companions to your monastery visit.

A warm Pastel de Belém is steps away — join the line, it moves quickly, and the first bite is sunshine.

Cultural & National Significance

Jerónimos is a compass for Portugal’s memory — a monastery turned national emblem, where voyages, faith, art, and language meet under the same vault.

It remains a living monument: carefully conserved, widely loved, and open to the slow step of visitors who carry Belém’s light onward.

Table of Contents

Royal Vow & Maritime Belém

At the dawn of the 1500s, King Manuel I chose Belém — the riverside threshold of Lisbon — to plant a monastery that would give thanks for voyages and pray for sailors. The Age of Discoveries had braided the Tagus to oceans; spices, maps, and stories returned to this shore, and a royal vow took the shape of stone.

The site mattered: near a small chapel where Vasco da Gama and his crew are said to have prayed before departure, close to shipyards and the river’s steady light. Jerónimos rose as both cloister and chronicle, a place to fold the sea into prayer and bind empire to responsibility. Manuel’s emblem — the armillary sphere — and ropes carved in limestone announced a maritime language made sacred.

Construction, Craft & Materials

Diogo de Boitaca began the work, his plan setting a wide‑armed church and a cloister that feels endless underfoot. João de Castilho carried the project forward with virtuoso carving; later, Diogo de Torralva and Jerónimo de Ruão refined proportions and classical accents as tastes shifted. Years stretched, stones stacked, and a style took on weight and grace.

Golden‑hued lioz limestone records the carvers’ patience: knots and ropes, coral and leaves, saints and royal signs. Vaults leap with startling lightness; columns unfurl like trunks into canopies. The craft feels intimate even at monumental scale — a city of detail you can read with your fingertips.

Manueline Language & Architecture

Manueline is not a single motif but a vocabulary: armillary spheres, crosses of the Order of Christ, twisted ropes, shells, seaweed, knots, pinecones, and fantastic creatures. At Jerónimos, this language blooms into structure — tracery and capitals, portals and parapets, all speaking of ships and scripture in the same breath.

The church interior makes stone feel light: a hall of branching columns whose vault seems to hover. The cloister turns the page and invites you to walk and read — shadow after shadow, arch after arch — until the sea seems to echo in the geometry. It is architecture as embroidery, faithful and fearless at once.

Prayer, Poetry & Symbols

Monastic life once wove the day here — bells and psalms, bread and study. Later centuries layered poetry and public memory: the tombs of da Gama and Camões in the church, royal burials in the chancel, and tributes that read like footnotes to a long maritime chapter.

Symbols abound but never shout: a rope can be a prayer for safe passage, an armillary sphere a map of wonder. Walk slowly; the carvings speak in a low voice, and the courtyard answers with light.

Secularization, Preservation & Restoration

Religious orders were dissolved in the 19th century; the monastery’s function shifted, even as its fabric remained. Earthquakes tested Lisbon, but Jerónimos endured with scars and grace. Restoration became a slow craft — cleaning, consolidating, and letting the stone keep its warmth.

Conservation here is a conversation with weather and history: joints repaired, carvings protected, drainage improved, access widened. The goal is legibility and calm — to keep the monastery readable without whitening away its years.

Ceremonies, Treaties & Memory

The monastery has hosted ceremonies of faith and state — from liturgical moments to cultural events. In recent times, it has framed European milestones, including the signing of the Treaty of Lisbon, binding the cloister’s calm to contemporary history.

Media and visitors carry these images outward: arcades, flags, and the river’s light. The building remains a setting for gratitude, debate, and quiet pride.

Visitor Experience & Interpretation

Guides and panels help decode Manueline motifs; audio tours stretch the thread from rope carvings to ocean routes. Families, school groups, and solitary wanderers find their own pace between sunlit stone and cool shade.

The rhythm of a visit is gentle: lower cloister, upper cloister, church, then a quiet sit on a bench. Interpretation favors clarity over noise, letting the monastery’s voice remain calm and kind.

Empire, Earthquake & 19th Century

Empire waned and Lisbon trembled in 1755; Jerónimos weathered shocks that leveled districts elsewhere. The 19th century brought secular shifts and a growing sense of heritage, with careful repairs and new respect for the Manueline voice.

By century’s end, restoration leaned toward revival and preservation. The monastery settled into its role as a national symbol — a patient witness to change.

20th Century: Nation & Heritage

The 20th century framed Jerónimos as cultural heritage as much as sacred space. In 1983, UNESCO recognized the monastery and Belém Tower, underscoring their global significance and maritime memory.

Conservation matured into a discipline of patience: surveys, gentle cleaning, structural care, and better visitor paths. The goal: keep the monastery alive and legible for everyone.

River, Route, and Global Ties

The Tagus is a chapter in the monastery’s book: ships slid past Belém with sails full and hearts uncertain. Jerónimos kept their names and prayers, anchoring a city to seas and stories far beyond its harbor.

Walking the cloister today still feels connected to routes that circle the globe — a reminder that stone can hold both home and horizon 🌍.

Women, Scholarship & Heritage

Modern scholarship widens the lens on monastic life, patronage, and the city around Jerónimos — bringing into focus the women who funded, worked, and interpreted this place across centuries.

The result is a richer story: not only kings and sailors, but artisans, scholars, and communities keeping a monastery alive in memory and care 🌟.

Nearby Belém Landmarks

Belém Tower (Torre de Belém), the Discoveries Monument, the MAAT and Berardo Collection, the National Coach Museum, and the riverside gardens make easy companions to your monastery visit.

A warm Pastel de Belém is steps away — join the line, it moves quickly, and the first bite is sunshine.

Cultural & National Significance

Jerónimos is a compass for Portugal’s memory — a monastery turned national emblem, where voyages, faith, art, and language meet under the same vault.

It remains a living monument: carefully conserved, widely loved, and open to the slow step of visitors who carry Belém’s light onward.